- Home

- Birkin, Charles

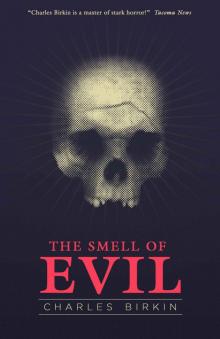

The Smell of Evil

The Smell of Evil Read online

THE SMELL OF EVIL

Charles Lloyd Birkin was born in England in 1907 and was educated at Eton College from 1921-1926. His contributions to British horror began in 1932 when publisher Philip Allan employed him to edit the Creeps series of short story collections, which included volumes with titles like Creeps, Shudders, Shivers, Nightmares, Tales of Death, and Tales of Fear. The books, with their sensational dust jacket art and stories by an impressive list of writers that included H.R. Wakefield, Lord Dunsany, Russell Thorndike, and Birkin himself (under the name Charles Lloyd), are highly collectible today and were the precursors of later popular British horror anthologies, such as the Pan Books of Horror Stories. Birkin’s contributions to the Creeps volumes were collected in his first book, Devil’s Spawn (1936), the only book published by Birkin before a long hiatus. In 1942, he succeeded his uncle as the 5th Baronet Birkin, and he served in the Second World War in the Sherwood Foresters.

Following a long break, Birkin resumed writing after his return to London in 1960 and, perhaps at the instigation of Dennis Wheatley, began publishing new collections of short stories with The Kiss of Death (1964), for which Wheatley provided an introduction. Several more volumes of tales appeared between 1965 and 1970, including The Smell of Evil (1965), also introduced by Wheatley. From 1970 to 1974 Birkin lived in Cyprus, which he fled in the wake of the Turkish invasion. He and his wife Janet spent their later years in the Isle of Man, where Birkin died in 1985.

John Llewellyn Probert is the author of five short story collections, including The Faculty of Terror, which won the Children of the Night Award, and its follow-up, The Catacombs of Fear. His latest books are the novella Differently There (Gray Friar Press) and The Nine Deaths of Dr Valentine (Spectral Press), which has been nominated for the British Fantasy Award.

By Charles Birkin

Devil’s Spawn (1936)

The Kiss of Death (1964)

The Smell of Evil (1965)

Where Terror Stalked (1966)

My Name is Death (1966)

Dark Menace (1968)

So Pale, So Cold, So Fair (1970)

Spawn of Satan (1970)

charles birkin

The SMELL OF EVIL

with a new introduction by

JOHN LLEWELLYN PROBERT

VALANCOURT BOOKS

Richmond, Virginia

2013

The Smell of Evil by Charles Birkin

First published London: Tandem Books, 1965

First Valancourt Books edition 2013

Reprinted from the edition published New York: Award Books, 1967

Copyright © 1965 by Charles Birkin

Introduction © 2013 by John Llewellyn Probert

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

Publisher & Editor: James D. Jenkins

20th Century Series Editor: Simon Stern, University of Toronto

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisher, constitutes an infringement of the copyright law.

isbn 978-1-939140-74-6

Also available as an electronic book

All Valancourt Books publications are printed on acid free paper that meets all ANSI standards for archival quality paper.

Cover by M. S. Corley

Set in Dante MT 11/13.2

A Very Elegant Cruelty: An Introduction to Charles Birkin’s

The Smell of Evil

Gentle reader, beware. Before you begin to read the stories that follow I feel it only fair to warn you. You are holding in your hands a book of some of the bleakest, most well-written, deliciously nasty horror stories you will ever have the good fortune to find on the printed page. Stories about wealthy, beautiful people capable of the most shocking acts of cruelty. Stories where the wide-eyed innocence of a young child can lead to the most horrible kind of death, either for the infant concerned or the adult who has unfortunately found themselves in the most macabre of situations. Stories of brutal revenge, of petty jealousies that culminate in the most grimly spiteful acts.

Welcome to the world of Sir Charles Birkin.

Charles Birkin inherited his title, becoming the fifth Baronet Birkin in 1942. Prior to this he had edited the Creeps series of horror anthologies for publisher Philip Allan during the 1930s. He was educated at Eton (1921-1926), and during the Second World War, he served as a Captain in the 12th Regiment of the 9th Sherwood Foresters. Following this he travelled widely, setting aside the writing career he had cultivated before war broke out.

The Smell of Evil was first published by Tandem Books in 1965 and was Birkin’s second volume of horror stories (after The Kiss of Death) to be published after his return to writing following a long hiatus. Dennis Wheatley is often cited as the man responsible for encouraging Birkin to take up his pen again, and it may well be that we have Wheatley to thank for the wealth of Birkin fiction we have available today.

In his original introduction to The Smell of Evil, Wheatley likens Birkin’s stories to those of Edgar Allan Poe. While this is high praise indeed, it’s neither a strictly fair nor reasonable comparison. Whereas much of Poe’s work arose from that author’s own tortured imagination, from within, if you like, Birkin’s fiction is very much a reaction to the external, to individuals and situations he must have encountered during his eventful life. Indeed, one can come away from the stories in this volume feeling as if one knows very little about the man himself, other than that he must have held a pretty low opinion of humanity. I would have loved to have met Charles Birkin, and I very much suspect that the man himself would have turned out to be far more affable and convivial than his works might suggest.

Birkin was very much a product of his education and his war experiences, and with the stories that follow having been written in the early 1960s, the reader of today is asked to exercise discretion in regard to many of the tales’ treatments of the working classes and those of foreign extraction. To be fair, it is not so much Birkin’s attitude in these stories that is prejudiced (unlike in the writings of Dennis Wheatley) but rather those of the characters he peoples his stories with, and which are no doubt a reflection of the times he lived in.

So what actually lies ahead of you? It would be unfair to spoil some of the treats Birkin has in store, but perhaps forewarned might allow you to be forearmed. The title story begins the book, and tells of the Baron and Baroness Lebrun, who move to an isolated cliff-top house near a Cornish village with their niece, Sari. We are informed, in typical Birkin style, that this poor young girl is unable to speak, could walk when she arrived but is now confined to a wheelchair, and was last seen at one of the house’s upper windows with tears streaming down her face. Oh, and Sari just happens to be heiress to the Lebrun fortune, which the Baron and Baroness would dearly like to get their hands on. Quite what they are doing to the little girl in an attempt to get her to sign over her deeds is so horrible that I am definitely going to leave you to discover it for yourself; suffice it to say that Birkin’s view of some examples of humankind is so bleak and bitter that you may well want to take a break and read something else before moving on.

I dare you to read the next story, “Text for Today,” and not imagine the author in church one Sunday as the verse in question from St. Paul’s Letter to the Corinthians was read out, only for him to then spend the afternoon trotting out this little tale of missionaries trying

to do good on some far-flung island and causing further horror instead.

“The Godmothers” starts off innocuously enough but becomes so grim that by the time bodies are being discovered you wonder if it can get any worse. And then it does.

“Green Fingers” is a classic World War II tale. All of Birkin’s stories set in Nazi Germany have a discomforting ring of truth about them (“A Lovely Bunch of Coconuts” is probably his best). What really causes the chills in this one, aside from the final revelation, of course, are the casual asides describing the “awful smell of the oily smoke” from the concentration camp crematoria “if the wind was blowing the wrong way.”

“Ballet Nègre” feels like it belongs in the 1965 Amicus anthology film Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors. As mentioned above, Birkin’s story itself isn’t racist, but his characters and situations definitely are, undoubtedly reflecting the mid-1960s cultural climate. His most cutting line, however, is reserved for the peroxide blonde prostitute who gets interviewed in a bar, “swinging her orange plastic handbag.”

Halfway through the book we get “The Lesson,” a personal favourite, and one I won’t say anything about, as you should discover Birkin’s deliciously observed infant-centred drama for yourselves.

“Is There Anybody There?” is about ghosts, and what makes them even scarier is that they can see and interact with you, telling poor old Millie that “they’re going to get her,” and they do, but not quite in the way you might expect. Even little old ladies living in country cottages are not exempt from the cruelty of Birkin’s world.

Another highlight is “Little Boy Blue.” Charming little sailor- suited Sammy died horribly, choking on quicksand while disobeying his mother. Eight year old Oliver now has an imaginary playmate. Is little Oliver destined to die the way Sammy did? Read on to find out.

“The Interloper” is set, rather curiously, on an island described as an “Adamless Eden.” We return to the theme of the concentration camp and you can probably guess what is going to happen to the man who turns up in the middle of the story wearing only his underpants, especially when it turns out he’s the son of a particular SS Commandant.

The volume finishes with one of Birkin’s regular, and often quite peculiar, science fiction tales. The only real purpose of “The Cross” seems to be to allow Birkin to go on about how nasty and unpleasant the human race is, just in case we haven’t got the point from the previous twelve stories.

Now, with your loins suitably girded and your sensibilities duly prepared (or at least I hope so) I shall leave you in the capable, cruel and supremely disquieting hands of a master of the short form.

They’re all yours, Sir Charles . . .

John Llewellyn Probert

September 5, 2013

THE SMELL OF EVIL

Contents

A Very Elegant Cruelty: An Introduction to Charles Birkin’s

The Smell of Evil

THE SMELL OF EVIL

TEXT FOR TODAY

THE GODMOTHERS

GREEN FINGERS

BALLET NÈGRE

THE LESSON

“IS THERE ANYBODY THERE?”

THE SERUM OF DOCTOR WHITE

“DANCE LITTLE LADY”

LITTLE BOY BLUE

THE CORNERED BEAST

THE INTERLOPER

THE CROSS

To

Dennis Wheatley

for all his kindly encouragement,

and for my daughter,

Mandy,

who was made to read them all.

THE SMELL OF EVIL

The first mention that I heard of Sari Lebrun was in the bar parlor of the Golden Ball where I was drinking beer after supper on the second evening of my holiday. The Golden Ball was the center of the social life of Trezarth, a tiny and unspoiled village on Cornwall’s southern coast, and it was remarkable only for having been run by the same family in whose hands it had remained for the past two hundred years. There were no innovations, no attempts at cuteness, no unfortunate contemporary influence, and no self-conscious artists’ colony to ruin it with their defiant bohemianism which, to my mind, can be the most irritating factor of all.

How it had escaped the exploitation that had done so much to spoil the neighbouring villages is unexplained, except that it is by no means easy of access to motor traffic and has never been written up.

There were only four guest rooms and a single somewhat primitive bath, in which an incautious movement while indulging in one’s ablutions often resulted in a scrape as from a nutmeg grater. There was always a smeared residue of sand on the peeling enamel, no matter what the season, and the wraiths of straps of dried seaweed seemed to haunt the tack marks in the recessed window embrasure which gave on to a small paved yard, nostalgic and kindly spectres of the bygone holidays of happy children.

Sam Varcoe ran the bar with the help of his son Luke, who was also a boat builder by trade, while his wife, Dorothy, and their seventeen-year-old daughter, Magdalen, did the cooking and the housework. They were a charming and unsophisticated family with whom it was a joy to stay.

It was the beginning of May when I arrived and the holiday season had not yet begun, in fact I was the sole guest. I had gone there to try and make a start on my second novel, and it was proving a difficult pregnancy. My first effort, Nuns on the Doorstep, had enjoyed a fair reception from the critics, if not quite so enthusiastic a one from the book buying public, and it had left me spent and drained of ideas, and my publishers had requested delivery of the new manuscript by the end of August.

Trezarth had a permanent population of about five hundred souls which increased during the summer months by maybe twenty-five per cent. The little fishing village was not spectacular like Mousehole or Helston and was, on the whole, rather down-at-heel, but for me it held great charm. There were few houses of any size in the surrounding countryside and, of the few that there were, Angdon alone was in the hands of “strangers”, having been let for a year to foreigners, presumed to be French or Belgians. They were a couple by the name of Lebrun, and the girl, Sari, was said to be their niece.

They had captured the imagination of Trezarth, for no one had met them. They had been observed from a distance, and of Sari it had been reported that not only was she an invalid but she was also reputed to be dumb, a combination which, together with her undeniable good looks, had aroused the interest and compassion of the villagers. This sympathy had been heightened by an incident which Dorothy Varcoe had herself experienced. Having spent a rare day in Penzance, where she had gone to purchase wallpaper, she had been walking home from the bus stop and had taken a short cut across the fields to a minor road which passed the front of Angdon on its way to Trezarth.

She had paused at the gate of the drive to admire a display of tulips which had come into flower when, happening to glance up, she had seen the girl at an upper window with the tears pouring down her face, apparently in great distress, and while Mrs. Varcoe was watching, her aunt, or stepmother, or whatever her relationship may have been, had come up from behind her, her face perfectly livid, and had wheeled her chair back until it was out of sight from the road. Mrs. Varcoe had been much upset by the girl’s patent unhappiness.

Baron François Lebrun and his wife seldom appeared in Trezarth, but the couple who looked after them occasionally toiled down the steep hill for minor purchases, although most of the supplies for Angdon were, or so it had been put about, obtained from Penzance which was some eight miles away, an arrangement which did not endear them to the locals.

“It’s a terrible thing about that poor girl,” Dorothy Varcoe said. “I’m always telling Maggie that good health is the chief blessing that the Lord can bestow. ‘Look after your health, Maggie,’ I say to her, ‘and you’ll have no worries that can’t be sorted out. Miss Lebrun now, with all the worldly advantages and th

e beauty of an angel—but an invalid! So what’s the use of it all?’ I ask her. And she always answers: ‘I know, Mother, you’re quite right.’” There was no cavilling to this truism that I could think of, and Mrs. Varcoe gave a final polish to the breakfast table. “When the Baron and the Baroness first came here the girl was able to walk about with a stick,” she said. “Tottery and slowly, I must admit, but she could move. Now I hear that she’s in a wheel chair all the time. Sounds to me as if she’s wasting.” She made a tutting sound. “I suppose they have had a doctor to her, but I’ve not heard so. Not Doctor Marreco, that much I do know, although if it was me I’d sooner call him in than any of your smart London specialists.” She seemed to be worried by this lack of elementary attention.

I was finding it hard to get started on the new book, probably because of the relentless approach of the stipulated and awesome deadline, and on the following afternoon I abandoned all attempts at work and went instead for a walk along the shore. The tide was way out, uncovering islands and archipelagos of weed-bearded rocks patterned with miniature lakes and pools that were encrusted with the pointed shells of limpets, and sea-gulls strutted arrogantly on the shining waste. It was a gray day, but warm and without a breath of wind. An hour’s walking and, it must be confessed, dawdling, for the attractions of marine life on the seashore have ever proved irresistible to me since my earliest days, brought me to the foot of a pathway that zigzagged up the cliff face and which led to the garden of a big house at its top, which I surmised correctly to be Angdon.

The Smell of Evil

The Smell of Evil